What's in a name?

why it matters what we call our food

To my delight, one of my all-time favorite videos recently made the rounds of social media again. It’s also one that my husband and I quote possibly more than anything else. It’s a clip from a 2010 episode of English daytime show This Morning, where regular guest chef Gino D’Acampo cooks up a pasta dish for hosts Holly Willoughby and Phillip Schofield. The segment shows D’Acampo preparing his Maccheroni ai Quattro Formaggi (or his “Ultimate Macaroni Cheese” as they call it on the show), a saucy penne dish with four cheeses and peas. At the end of the cook, D’Acampo serves up the pasta to the hosts, and after general comments about the deliciousness of the dish, Willoughby offers the fatal commentary: “Do y’know, if it had like, ham in it…” (cut to D’Acampo’s horrified face here) “…it’s closer…” (Schofield starts saying “oh no, oh no” in the background) “…to a British carbonara.”

The show then cuts back to D’Acampo’s absolutely flabbergasted, mouth-open-in-shock face, which becomes dejected as Willoughby doubles down, and he finally sputters out the infamous line:

Of course, this sets Willoughby and Schofield into fits of hysterics, and continues the ongoing banter that D’Acampo and the hosts were known for over the course of the years they did this segment together. It is a truly hilarious moment, not just because of the absolute horror in D’Acampo’s expression, but also because the hosts know that some sort of outburst of disgust is imminent. What many people watching this don’t know is that D’Acampo has actually used an Italian saying: “e se la mia nonna avesse le ruote sarebbe una carriola” or “and if my grandmother had wheels, she would be a wheelbarrow.” So still very funny, but he didn’t create this famous utterance out of thin air.

This really is one of our favorite videos and quotes, but it also has a deeper meaning to me — does it matter what we call our food?

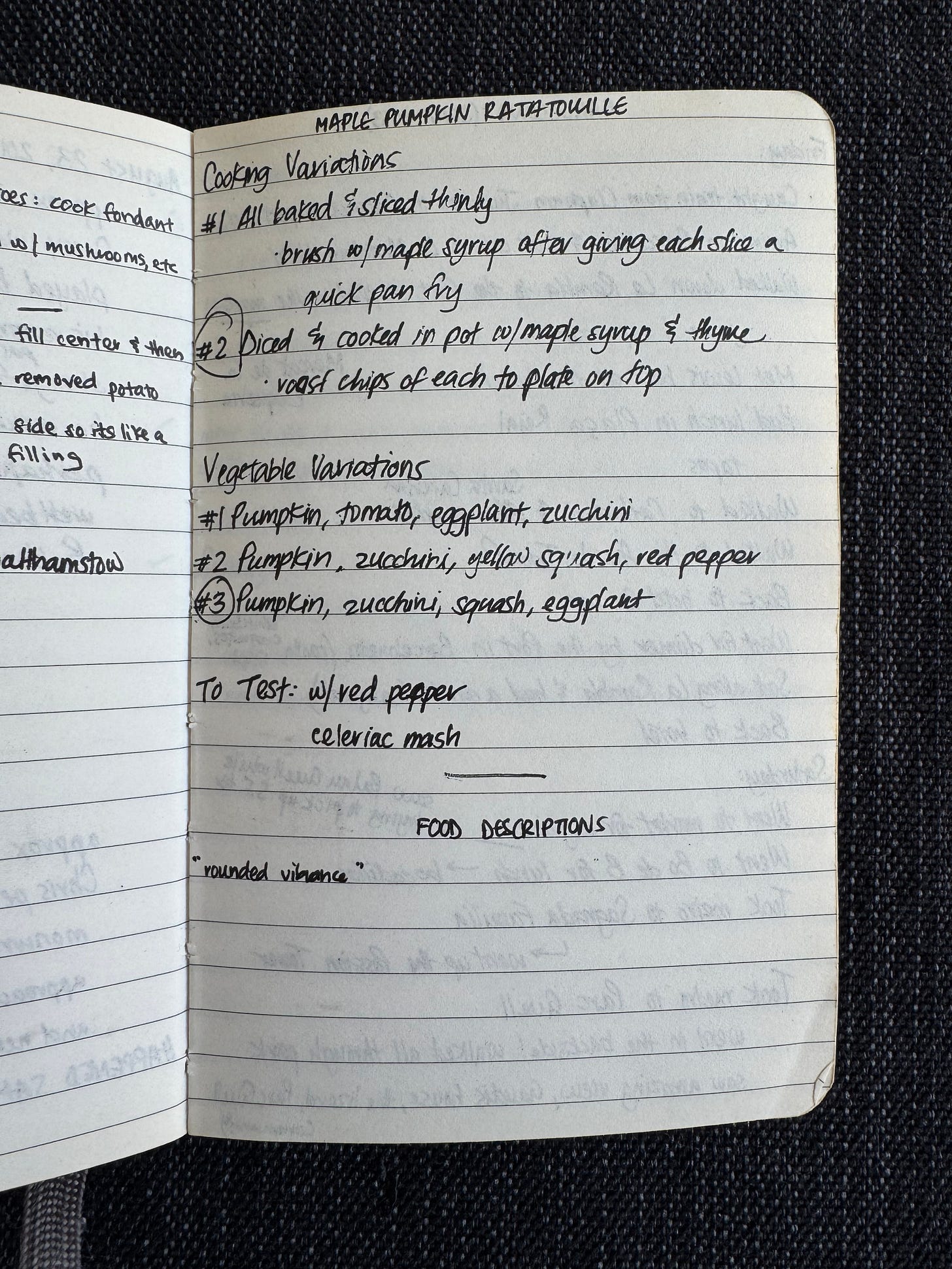

When I was in my last term of culinary school, we finally got to start creating our own dishes. For one class, I was working through an idea of a maple pumpkin ratatouille, and was explaining it to my chef instructor. “It is an interesting idea, but you cannot call it a ratatouille,” he told me. “The appellation matters, and if you put maple and pumpkin in, it is not a ratatouille.” At the time, I tried to elaborate on why the method of cooking made it a ratatouille, especially considering the wide range of versions of ratatouille around France. But he was very firm, repeating that I could call it something else, but “not the appellation ratatouille.”

Coming from Los Angeles, a city where it’s not only easy to find almost any cuisine your stomach may desire, but also fusions of those cuisines, I struggled to understand why this was such a hard line for my chef. Even to this day I see menus where there are liberties taken with descriptions of dishes.

There are two parts of this conversation in my opinion. The first is represented by my “maple pumpkin ratatouille: should we be using familiar dish names more freely or not? We have already decided that many foods must have specific origins to be allowed to use certain nomenclatures. The certifications you find across Europe such as France’s AOC (appellation d’origine contrôlée), Italy’s DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata), or even the EU’s overarching AOP/PDO (appellation d’origine protégée/protected designation of origin) have become common enough that we don’t even question them. We have no problem identifying that real champagne comes from Champagne, even if we use the name more broadly. We know one of the reasons that jamón ibérico costs more is because it can only be made in Spain.

On the flip side, we do also commit my chef's sin of mis-appellation regularly. Hummus is an excellent case: with seemingly unending varieties these days, not only in flavors, but in base ingredients from black bean, to edamame, and even sweet versions like chocolate brownie, is the marketing choice of classifying all of these dips as “hummus” right? Hummus is its own dish, and one that holds a fundamental place in many Middle Eastern cuisines, so why are we calling dips that have no relation to this dish, aside from the texture, “hummus”? We already have the perfect term in our culinary language to describe these dishes without appropriating hummus: puree. And yet, the assortment of “hummuses” grows.

Furthermore, the use of incorrect food names can obscure the real culture behind these dishes. One of the most well known examples of this erasure is the Alison Roman curry vs stew debacle. This brings to the forefront the more insidious aspect of all of this: cultural appropriation. The history of humanity is the story of foods being taken around the world and incorporated into other cuisines, but at this point, with a more global perspective, there isn’t an excuse for introducing an ingredient or technique as novel if a whole culture is already using it. Acknowledging that it is new and remarkable to you is one thing, but we have reached a stage where so much information is easily accessible to us that doing a little research to honor the origins of a food should be a given. This is all especially important because the foods that tend to get erased are the foods of people who are discriminated against or overlooked. #TheStew, as the internet dubbed Roman’s culinary whitewashing, was the catalyst that began this long overdue conversation, written about excellently in this piece for Eater by Navneet Alang. Of course, while we have started talking about this, we’ve barely scratched the surface of putting our money where our mouth is, literally, by supporting non-white voices and hands in the predominantly white culinary scene in America.

This is where we return to D’Acampo and his pasta dish that is NOT a British carbonara. While I don’t believe anyone can argue that Italian food has experienced any sort of erasure, it is still important to recognize that names matter. His Maccheroni ai Quattro Formaggi actually has none of the distinguishing ingredients of carbonara, namely eggs, guanciale, or pecorino romano. And while I think there is an argument to make of using familiar dishes to describe unfamiliar ones, to create a foundation that lets an eater understand and recognize something new, it isn’t enough. It’s one thing to say, “it’s black bean hummus!” and another to say, “this pureed black bean dip has the texture of hummus,” or “this chickpea stew has warm, aromatic spices” and “this chickpea curry is stewed with spices and flavors from South India and the Caribbean.” One way provides a basic, almost meaningless sketch of the dish, and the other actually provides a description, and honors the true meaning of a dish.

In the years since culinary school, I have come to understand much more where my chef was coming from. I thought it was that he was a rigid French chef too focused on classical food rules, but I now appreciate that, for many reasons, it does actually matter what we call our food.

For this month’s recipe, I’m giving you my regular, not maple pumpkin, ratatouille. One of the first dishes I ever learned to cook, ratatouille is one of my most favorite meals (and one of my favorite movies!). In fact, the first thing I ever cooked for my husband back when we started seeing each other was a ratatouille with fish. “I hate tomatoes, and I don’t like fish,” was said with horror on his face, and I was pretty sure that that was the end of that. Twelve years later, he’s still slightly annoyed when I make ratatouille, but I’ve never seen anything but a clean plate after dinner.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Cornivore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.